Deconstruction of Inner Images: Writing and Conception in Yang Liming's Paintings

He Guiyan

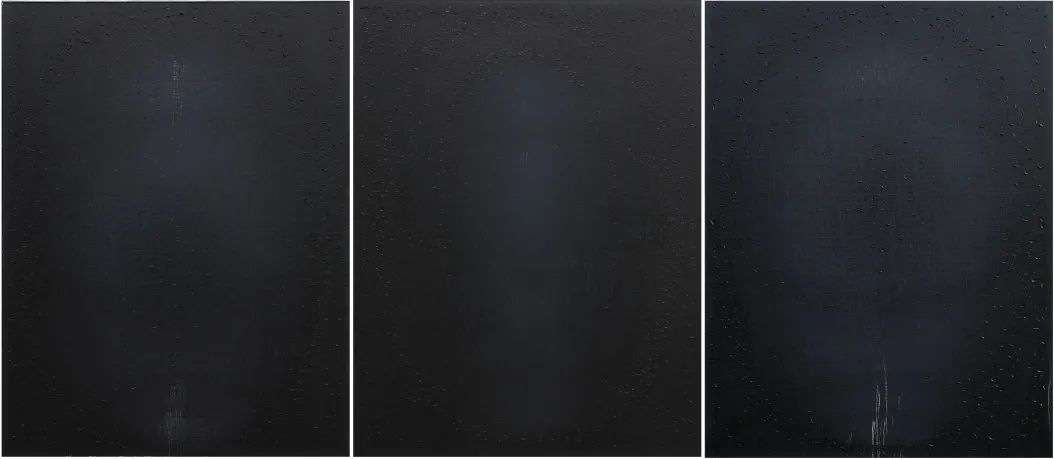

The paintings of Yang Liming can be roughly divided into three series: Blue, Black, and Red. Although the classifications of the artist’s works were seemingly determined by their overall hues, these series chronicled the artist’s development in three succeeding phases. Taking the year 2005 as a demarcation, the works from the early “Blue Series” fixate on an abstract aesthetic that centers on the tonal atmosphere and calligraphic gesture of the compositions. In comparison to the “Blue Series,” the subsequent “Black Series” seems to be purer, and in terms of the series’ pictorial language and rhetoric, the artist has continued to infuse them with a plethora of Eastern visual characteristics. Under Yang Liming’s rendition, the black becomes an extremely dramatized element. Given the enormous scale of his paintings, the color fields painted in black engulf its audiences with an aesthetic experience that is both aloof yet sublime, desolating yet melancholic. The formation of the black color fields in his works was not only a result of the artist’s relentless stylistic development but also directly inspired by “Color Field Painting,” a style related to American Abstract Expressionism. Unlike the purist approaches of European and American abstract art, the “black color fields” in Yang Liming’s compositions differ in their structural development and linguistic logic. His works are not only visual but psychological—a kind of metaphysical world constructed by the East. Even though such a world is rather an ineffable concept, the artist can interpret and immerse in it through his personal expression. To disrupt the formal and structural autonomy of the “black color fields,” Yang Liming has intensified the Eastern aesthetic ideal of “ink encompasses all five colors.” At the same time, he highlighted the calligraphic nature of his works, as this kind of calligraphic expression originated from the artist’s Eastern cultural experience—which incorporated the gestural nature of calligraphy and the expression of line, ink, and rhythm in traditional Chinese painting.

Perhaps, the “Red Series” is a continuation and deepening of the “Black Series,” with the artist emphasizing more on the conceptual expression sustained by language and form. The starting point of the transformation is rooted in the logic that engenders the compositional format. There are two paths in the development of abstraction in the Modernism of the West. The first one is the “significant form,” which emphasizes the artist's formal refinement and transformation of external or real objects to grant them abstract characteristics. The other is the emphasis on "self-regulation of language" and "self-critique" of form, that is, starting from the internal logic of form and language. The language of Yang Liming's paintings originates from gestures, but the ultimate goal is not the content of the gestures but the fact that such gestures inject new meaning into the form. For Yang Liming, the content of his gesture is not important, but it’s more of an everyday meditative act. The traces of mark-makings left behind became a witness of the artist’s presence. They imbue in the works a unique emotional experience, as gesture itself as an action is often accompanied by a variety of emotions, bestowing the lines with different expressive powers. Also, the calligraphic gesture is an experience of time, through which the repeated mark-making, repainting, superimposition, and concealment of lines will grant a work a sensibility of time and space. Judging from this point of view, the essence of Yang Liming’s art has nothing to do with abstract painting of the West. It instead gears towards conceptual painting. The process, physicality, and contingency in calligraphic gestures introduce more formal possibilities to the works.

In the recent “White Series,” Yang Liming has taken another forward. The language of these paintings also references calligraphy—a gesture that allows him to convey his inner experience, but the visuality and formal expansion of the compositions have undergone a fundamental transformation. In contrast to the “Black Series” and “Red Series,” the “White Series” unfolds from the outside to the inside, from space to plane. The elusive, mysterious aesthetic experience from his previous works has weakened to give way to the materiality and tactility of the composition. The ever-expanding lines in these works transform into calligraphic traces. The emphasis on flatness and materiality implies an insistence on gesture that symbolizes the formal expansion and flow of emotions. Such formal expansion and layering of colors also imply the enrichment of values. For the audiences, the white color fields and the ghostly lines path the way for them to enter the artist’s painterly world.

Since the Pre-Qin period, the ancient Chinese already proposed that “the sage imitated the images of all created things to express his own intentions fully.” During the Wei and Jin Dynasties, the idea of “acquiring meanings by relinquishing forms” has somehow morphed into a leading principle for artistic creation. In other words, it bases on the artistic and cultural spirit of China, and in the field of painting, its transcendence of the aesthetic subject and its pursuit of spirituality and artistry have never escaped the “image” and “form.” Unlike how Western modernist abstraction’s conflict between subject and object, Chinese artists, on the one has, have to come up with a personal style and a creative methodology, and on the other hand, they need to achieve an “intersubjectivity” between the subject and object through their painterly languages, extracting from it the cultural and aesthetic values. In the sense that the exhibition with his knowledge in the Chinese art and aesthetic culture, “Deconstruction of Inner Images,” reveals how Yang Liming constructed his painterly world through a contemporary artistic language and conceptual expression.