Critical Review

Exhibition Statement|Dust and Wild Horse: Wu Weijia's Philosophical Painting Realm

2025.09.21

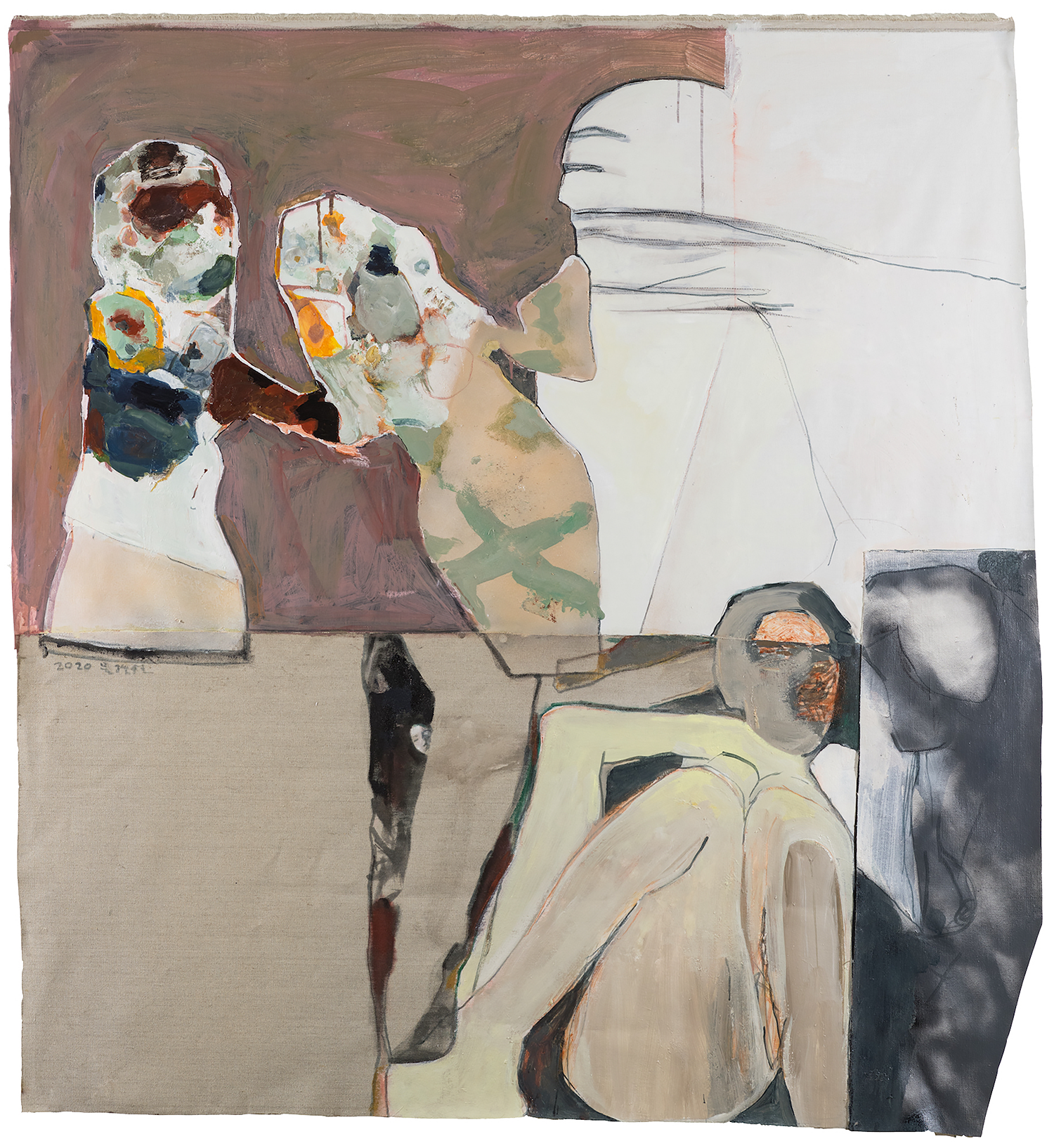

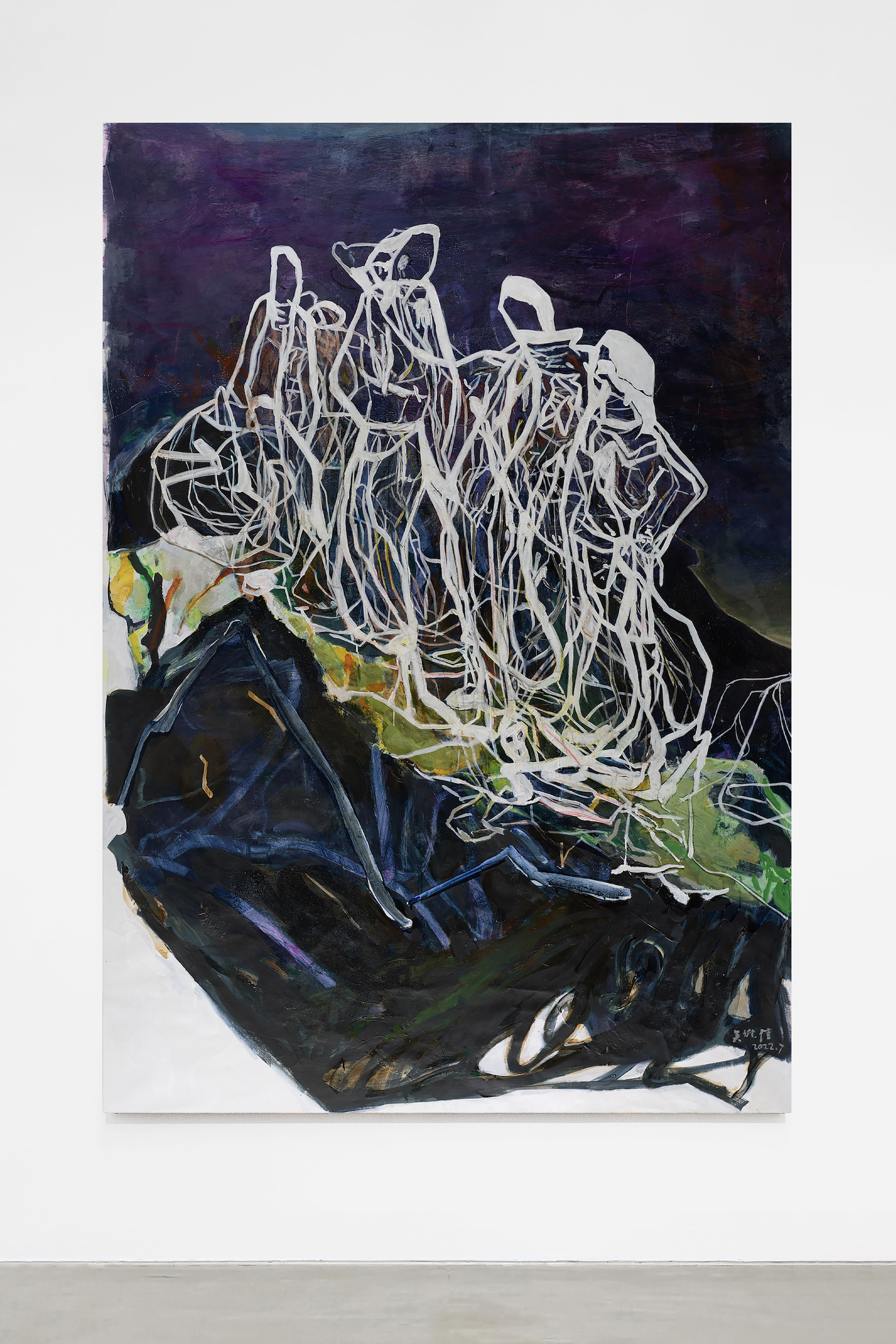

Exhibition Statement Dust and Wild Horse: Wu Weijia's Philosophical Painting Realm Text / Wang Jiang

Breath surges and swirls, now wild horses, now dust, images combining in unimaginable forms. Gathering and dispersing, parting and reuniting, cycling endlessly. This spectacle now manifests in Wu Weijia's recent works. Based in Nanjing, he is past sixty. His creative thought shuttles between East and West, their distinctions no longer posing any trouble for him; rational deliberation gradually gives way to perceptual intuition. When logical argumentation can no longer satisfy the deepest spiritual yearning of the human heart, a profound intuition nourishes vast insight. Uninhibited, free, and self-content. The creative process is like a spiritual practice; the picture thus moves towards expansive realm. The artist no longer resides externally making seemingly objective analyses; he perceives the origin of existence from within. Therefore, the images we see are not enticing intoxicating surfaces; they are artistic conceptions and sensations concerning “Suchness”. These images are mysterious yet not obscure in the least, touching upon the actual operation of life's reality. In the instant before the spiritual eye opens wide, these paintings might still seem like enigmas. And Wu Weijia, with Zen-like intuition, leads us into the realm where both object and self are forgotten, presenting to the viewer that all is just as it is. 01 Blown by Breath · Generation and Flux "Wild horse, dust,—living things blow breath upon each other." Dust and wild horse, one still, one moving, reflect from Zhuangzi's realm of carefree wandering into Wu Weijia's pictures. Two seemingly unrelated things are, in reality, both connected to breath. Dust is slight, floating on the wind. Regarding "wild horses," most historical commentaries explain it as the floating *qi* (energy/air) between heaven and earth. Wandering mist, steaming and floating, its form like wild horses galloping. The term "wild horses" also often appears in later Buddhist classics, pointing to a landscape like this: heat haze like drifting threads, shimmering in the deep desert, within that mirage are woods and springs. Yet, once the observer approaches, the scene vanishes. A mirage, indicating illusion cannot endure long. The essence of wild horses is also dust – dynamic microscopic particles. Dust settling and condensing symbolizes the decline of life; wild horses steaming and expanding signify the sprouting of vitality. Thus, dust and wild horses are related through mutual interpretation, not simple juxtaposition. The animating breath of life is itself a flowing breath. Dust gathers and scatters impermanently, just like the cycle of life and death. Wu Weijia titled one of his new works "Dust Wild Horses." Regarding this, he admits any of his paintings could bear the same name. Because that opening wise statement articulates his fundamental perception of the world. On his canvases, all things are simultaneously generating and vanishing. Form and color no longer seek a final, settled outcome. Still recognizable images and unrecognizable outlines and smears bring deliberate semantic openness. Various images always seem difficult to reconcile. Perhaps this is precisely a kind of "embracing incompleteness" wisdom. Traditional painting involved first analyzing and deconstructing images, then reassembling them intellectually. Now, Wu Weijia follows the original appearance of things to perceive them. Reason knows its own "unobtainability" (Anupalabdha); art should not be bound by form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and the Five Skandhas. Thus, the eye no longer fixates on fragmented appearances. When visual arrogance is eliminated, the inner sense awakens. The true meaning that "all is illusory, hence all is empty" becomes manifest before us. Zen Master Deshan Yuanmi said: "Only investigate live utterances, do not investigate dead utterances." Dead utterances usually have a logical path to follow, often an interpretation to seek. Conversely, words and states that surpass linguistic and conceptual discrimination are live utterances with no interpretable solution. Wu Weijia often cites this phrase when discussing his work. For him, painting is his practice. He to the greatest extent possible relinquishes the initiative of the will; intuition is released from the governance of intellect, revealing the spiritual activity hidden deep within. Those eyes accustomed to seeking binary oppositions and mutual differences will meet frustration here. His painting is like a live utterance, flowing freely between the states of dust and wild horses. The painting is inherently tranquil, seemingly contemplating eternity. But the artist's brushstrokes are like wild horses, penetrating dead wood and cold ashes, carving streaks of spiritual light. These pictures seem to exist in the interval between our seeing lightning and hearing thunder – a silent roar, a monumental immensity poised to arrive at any moment. 02 Unifying Things through Perception · Equal Insight The elements entering the painting originate from encounters and sights in the artist's life. He takes them freely, following his heart's desire, without adhering to specific selection criteria. He has no preconceptions about what content the picture can bear. However, this does not mean the picture is merely a collection of re-presentations of real-world counterparts. On the contrary, Wu Weijia adopts a direct way of looking, a viewing subservient to intuition – this is a mode of perception. He places something directly before our eyes, thus manifesting the thing itself. Simultaneously, he never compares the things entering the painting. Nothing is higher than anything else, and nothing is truly insignificant. All subjects are placed on an equal footing – this is the unification of things. When humans are self-centered, they define and use things based on their function and utility. Unifying things requires understanding the process of a thing's becoming the thinging of the thing. Wu Weijia's view of unifying things creates a vision that re-insights all things, dispelling the representational system that sustains illusion. Viewing things through things, he rescues things from the artificial system of naming. Borrowing Buddhist terminology, this is "breaking names and forms". Here, the artist is no longer a prisoner of language; he must break the established order constructed by names and forms, restoring those things firmly bound to them. Those likes, dislikes, rights, and wrongs fixed upon a pathological consciousness hinder people from entering true inner freedom. In contrast, the images in the artist's recent works are no longer mirrors of any reality, nor even psychological impressions. The opposition between thing and self is transcended; the creator's own existence is also part of all things; the unilateral control humans exert over things becomes cautious and restrained. Through both recognizable and unrecognizable images, individual judgment recedes to the maximum extent. The viewer enters the wondrous state of effortlessness, allowing themselves to dissolve into the unity of all things. Unifying things does not intend to erase differences between things; it emphasizes that each thing and its uniqueness must be respected. The vast majority of things lurk silently around us, unnoticed. But Wu Weijia gathers these things in a "readiness-to-hand" state together equally. Images interlock in indescribable states, spreading out what Gilles Deleuze calls a "plane of immanence". On this plane, inside and outside are identical; small and large are relative; signifier and signified unite. Lines and color blocks on the canvas constantly overlay; images also move from concrete to abstract, from being to non-being. Equal things weave a net, bearing the continuously increasing weight of concepts. On this net, every thing and every node is the center, connected to the whole world. This resembles the often spoken by Buddhists: a mustard seed can contain Mount Sumeru. 03 Envisioning through Insight · Intuitive Representation The definition of image is rewritten in Wu Weijia's recent works. Typically, understanding images follows two types of logic: First, materialists see the image as subordinate to some objective reality, a copy where the replicated original is more crucial. Second, idealists consider the image a transient picture in the mental world, the imagination and re-presentation of experience and perception. Such dichotomies – inner/outer, spirit/matter, subjective/objective – are so deeply ingrained that proponents of materialism and idealism cling to their own views, locked in stalemate. However, the Image in the context created by Wu Weijia is an existence both greater than illusory representation and lesser than a thing (Chose) with a definite essence – this aligns with the theory of the "image" pioneered by Henri Bergson in Matter and Memory. The image primarily requires people to set aside preconceptions and use intuition to apprehend. The "I" here is no longer aloof, no longer trapped in the endless sophistry of traditional philosophy revolving around stark opposites. Currently, we live in a craze of infinitely pursuing visibility. Like the late 19th century, the proliferation of images again weakens the viewer's confidence. The mechanical eye seems to possess greater certainty, while the fleshly eye becomes obsessed with various forms of voyeuristic tools. Western modernism also fermented and emerged against this background. Wu Weijia, who experienced the baptism of the '85 New Wave and culture fever of the 1980s, is certainly very familiar with the intellectual approach of modern art. Today, he redevelops the potential anti-oculareentricism within history, explicitly resisting the violence of the technological eye. The universe within his paintings consists of self-sufficient images; although they are the interface where perception occurs, they do not lead to any rational cognition. On the contrary, perception restores freedom to the bodily senses. Unlike the increasingly popular theme of contemplating the flesh, Wu Weijia regards the body as the foundation and tool of action and perception. The entire body, including the brain, no longer serves any representational purpose, nor does it provide redundant explanations of outcomes. It is merely about feeling, genuine feeling. The super-consciousness experience concerning the image can be termed "awaking" in Zen Buddhism. Using intuition to sympathetic with the observed object, thereby dismantling the barriers set up by linguistic analysis, symbolic thought, and visual representation. The highest state of awaking is emptiness; Wu Weijia uses this emptiness to refuse the homogenizing tendency of contemporary art. He adopts a set of negative strategies, allowing previous observers to identify some "bad painting" elements. For instance, chaotic imagery results in no clear focal point in content; fragmented image segments often disrupt the viewer's newly gathered attention. He deliberately avoids the stage of perfect completion; constantly overlaid glazes are destructive; deliberately left fissures carve out awkward rhythmic pauses. The failure of appearance becomes the endpoint of the painting; the absence of meaning leaves room for thought and judgment. This negative path resembles what the ancients called "clarifying the mind"; it endows the picture with an affirmative and open vitality, subsequently inviting the viewer to "savor the image" through insight. 04 Engaging Zen through Enigma · Riddles and Realization Wu Weijia once compared his encounter with images to the "blind turtle and floating log" from the Saṃyukta Āgama. Only in a chance instant can the blind turtle meet the floating log in the vast ocean. The artist patiently awaits that opportune moment, that moment which awakens inner perception. From a psychoanalytic perspective, we could also say fluctuations of the subconscious create psychic drives. This force causes images to deform, yet simultaneously creates connections between irregular parts. Images twist together, forming a puzzle that logic cannot tame. Wu Weijia abandons metaphysical semantic structures; his art enters the mysterious Zen state. Based on decades of accumulated Western painting techniques, he breaks through stylistic conventions, constructing a unique formal system through Eastern Zen insight. As his senior Su Tianci once commented, he paints according to his innate nature, forming his own system, possessing an artless beauty. Zen focuses on the true reality of all dharmas. In comparison, reason captures only clumsy appearances. Therefore, in Wu Weijia's painting process, correction and negation constantly play out. Countless different lines overlay; the initial starting point has already blurred. The picture only serves as a certain cause, but does not promise the fruit others expect, much less promise to lead one into a specific reality. Traces that appear to be trauma, rupture, and damage are deliberately preserved or even highlighted. In the artist's own words, the final presentation of the picture is "the wreckage of war." The war mentioned here is the breaking of self-attachment. Zen is mysterious and unpredictable; it cannot be clearly explained by words or reason. Historically, Zen wisdom often relied on "koans" – anecdotes recording the seemingly paradoxical "questions and answers" of Zen masters. The responses of the enlightened to questions are always concise and direct, never beating around the bush, nor hesitating for a moment. Wu Weijia's recent works are precisely the "Zen phrases" and "koans" he paints. The pictures cast aside words and concepts, returning to intuitive perception itself. That is the perception that occurred before consciousness existed – the unconditional, undifferentiated, and point of origin surpassing any limitation. These pictures have subtle and profound charm, inevitably reminding one of the haiku written by the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer. When composing haiku, the poet develops his sensations into images, then develops the images into words. The words follow rhythm to translate those images. Similarly, the images on the canvas are like diction, just as unrelated words collide within the fixed structure of a haiku. The juxtaposition of images is precisely the deliberation in arranging words. Thus, sensation and image blend into one, no longer relying on words, no longer circuitous. Den stora gåtan – Tranströmer's collection of haiku used this title. For Wu Weijia's recent works, using this phrase is equally quite fitting. At the intersection of Eastern and Western civilizational gazes, Wu Weijia's dust and wild horses are full of spiritual dynamism. Wonderfully, this dynamism instead allows the viewer to find a trace of tranquility in the highly uncertain present, because these great enigmas are by no means products of agnosticism. Like many Zen koans, only in intuition can the enigma be easily resolved. "Dust and Wild Horses" deliberately distances itself from representation and rational logic, evoking a purer and more thorough realization. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Artists

Wu Weijia

Wu Weijia, born in 1960 in Nantong, Jiangsu Province, graduated in 1982 from the Oil Painting Department of the Fine Arts School of Nanjing University of the Arts, where he studied under Su Tianci. He currently lives and works in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, teaching at the School of Fine Arts of Nanjing Normal University. He has long been engaged in painting instruction and artistic creation.

Throughout his artistic career spanning over four decades, Wu Weijia has dedicated himself to painting practices across various media, including oil painting, Chinese painting, and calligraphy, demonstrating exceptional artistic talent and mastery. His works are housed in the collections of several major art institutions, such as the National Centre for the Performing Arts, the Jiangsu Art Museum, and the Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts.Wu Weijia (b.1960), was born in Nantong, Jiangsu Province, and currently lives and works in Nanjing, China. For over 40 years, his artistic creation has spanned Chinese and Western art forms, achieving excellence in oil painting, watercolor, Chinese painting, calligraphy, and seal - carving. Throughout his artistic career, his style has been diverse yet consistently unique. This style stems from his deep - seated drive for artistic innovation and exploration, combined with his ability to express genuine artistic pleasure. In 1995, Wu Weijia visited the US and Canada with a delegation and exhibited his works there. Over the years, he has been a active presence in the art world, holding solo and group exhibitions in various places such as Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Jinan, Zibo, Taiwan, and Macau. His works are collected by many important art institutions, including the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Jiangsu Province Art Museum, Nanjing University of the Arts Gallery, and Tianning Zen Temple.

Throughout his artistic career spanning over four decades, Wu Weijia has dedicated himself to painting practices across various media, including oil painting, Chinese painting, and calligraphy, demonstrating exceptional artistic talent and mastery. His works are housed in the collections of several major art institutions, such as the National Centre for the Performing Arts, the Jiangsu Art Museum, and the Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts.Wu Weijia (b.1960), was born in Nantong, Jiangsu Province, and currently lives and works in Nanjing, China. For over 40 years, his artistic creation has spanned Chinese and Western art forms, achieving excellence in oil painting, watercolor, Chinese painting, calligraphy, and seal - carving. Throughout his artistic career, his style has been diverse yet consistently unique. This style stems from his deep - seated drive for artistic innovation and exploration, combined with his ability to express genuine artistic pleasure. In 1995, Wu Weijia visited the US and Canada with a delegation and exhibited his works there. Over the years, he has been a active presence in the art world, holding solo and group exhibitions in various places such as Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Jinan, Zibo, Taiwan, and Macau. His works are collected by many important art institutions, including the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Jiangsu Province Art Museum, Nanjing University of the Arts Gallery, and Tianning Zen Temple.

Learn more >

Related Contents